Author: Willem Ligtvoet, Vincent van den Bergen

Dossier: Water als prioriteit op de internationale agenda

Editor: Vincent van den Bergen en Willem Ligtvoet

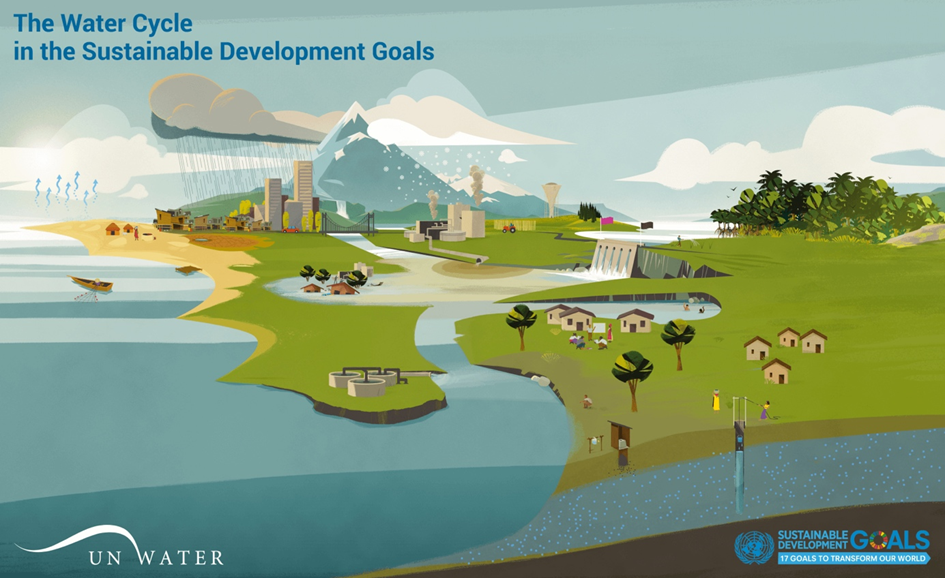

Water is critical for all life on earth and flows through all the SDGs. The Global Commission on the Economics of Water argues that the global water cycle is critical in dealing with the looming global water crisis, that the water cycle should be considered as a global common good, and calls for an economic transformation in valuing water. Will the UN System-wide Strategy on Water and Sanitation take up the gauntlet and structurally bend the trend?

Heading for a global water crisis

Water is a prerequisite for life and everything on earth is linked to water and the hydrological cycle. But water can also be a threat: tropical storms, flooding from rivers or sea, extreme rainfall, heatwaves, droughts and wildfires and pollution are inflicting an increasing toll all over the world. Today, globally four billion people are experiencing clean water scarcity for at least one month in a year and population growth, economic development and climate change increasingly strain the available water resources. Science and evidence from around the world show that we are heading for a water crisis, local, regional and global. This looming water crisis is intertwined with global warming and the depletion of biodiversity and demands for an urgent and systemic approach. However, despite its critical importance, the value of water is still largely overlooked in economic, societal and political strategies and decisions. Against this background, in May 2022, the Global Commission on the Economics of Water (GCEW) was established, initiated by the Government of the Netherlands as co-host of the UN 2023 Water Conference.

The Global Commission on the Economics of Water 2022-2024

The task of the GCEW was re-envisioning the economics and the valuation and governance of water so as to achieve a sustainable, just and prosperous future for all – a truly ambitious assignment! The GCEW was led by four co-chairs representing a diverse group of policy leaders and experts, with strong representation from the Global South. The GCEW’s work and recommendations were independent of the Government of the Netherlands and of any other public authority. Its two-year mandate ended in October 2024, with the publication of the final report The Economics of Water – Valuing the Hydrological Cycle as a Global Common Good. In this comprehensive final report, in line with many other studies, the GCEW underlines the critical role of water and the water cycle in and for the world, and emphasizes the need for a fundamental change in the economic appreciation of water.

Five main takeaways

1. Consider the global water cycle as a global common good

In its final report the GCEW focusses on the hydrological cycle, arguing that ‘Our policies, and the science and economics have overlooked a critical freshwater resource, the “green water” in our soils and vegetation”, as opposed to “blue water” from rivers and lakes. The report found that water moves around the world in “atmospheric rivers” which transport moisture from one region to another (figure 1). About half the world’s rainfall over land comes from soil moisture and healthy vegetation in ecosystems that evaporates and transpires water back into the atmosphere, generating moisture flows and rainfall across the globe. China and Russia are the main beneficiaries of these “atmospheric river” systems, while India and Brazil are the major exporters, as their landmass supports the largest flow of green water to other regions. Between 40% and 60% of the source of fresh water rainfall is originating neighboring regions and strongly depending on land use, including in neighboring countries. Current land-use developments across the globe such as deforestation and soil degradation in combination with climate change increasingly threaten the global and regional water cycles and for the first time in humankind history the hydrological cycle is out of balance. Water and the global water cycle, therefore, should not be regarded as an endlessly renewable resource, but as a global common good, the GCEW states.

2. The climate crisis is intensifying water scarcity and flooding

The impacts of the climate crisis are experienced all over the world and in the global and regional hydrological systems, facing severe disruption or even collapse. Drought in the Amazon, tropical storms and hazardous rainfall across oceanic islands and coastal zones of eastern USA, floods across Europe and Asia, glacier melt in mountains and numerous other examples show the effects of extreme weather events, likely to get worse in the near future. People’s overuse of water, diminishing vital water resources, and land reclamation also worsen the climate crisis, for instance by draining carbon-rich peatlands and wetlands, resulting in the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

3. Water is too cheap for some and too expensive for others

The value of water, the earth’s most precious resource, is not reflected in today’s economic and political practices. The commission stipulates that pricing of water should be used in such a way as to incentivize efficient and equitable use and not to the advantage of a few and the disadvantage of a majority. Ensuring its critical role in sustaining all other natural ecosystems means that in particular the largest water users and polluters should be targeted, taking their responsibility seriously. Subsidies to agriculture (and other economic activities like energy) around the world often have negative consequences for water, providing for instance perverse incentives for farmers to raise crops that need large amounts of scarce water resources and use water wastefully. Industries also have their water use subsidized, or pollution ignored. As a consequence, poor people in developing countries frequently pay a high price for water or rely on unreliable sources. Removing harmful subsidies combined with protection of the vulnerable people and ecosystems must be a priority for governments. Additionally, low-income countries must acquire better access to finance in order to provide safe water and sanitation, and halt the destruction of the natural environment.

4. To turn the tide requires an economic transformation

The urgency for change is evident and the cost of inaction is high. High-income countries could see their GDP shrink by an average of 8% by 2050, while lower-income countries could face even steeper GDP declines of 10-15% if the water problems are not adequately solved. Taking a broad view of what constitutes the ‘economics of water’, the most new and overarching message of the commission is that the global water cycle is of critical importance and needs to be valued and governed as a global common good. To account for the importance of water the GCEW states that a new paradigm of the economics of water is needed, encompassing:

- Recognising the water cycle as a global common good and cross boundary partnerships to protect watersheds and waterflows.

- Transforming governance of water at systems (local to global) boundaries rather than political boundaries.

- Valuing water properly to reflect its scarcity and the ecosystem services it provides

- Internalising economic externalities.

- Incentivising innovation and capacity building in the entire value chain.

- Recognising that the costs of inaction far outweigh the actual costs.

Valuing water is a critical issue and desperately needed. In 2018, the High-Level Panel on Water (HLPW) launched the Valuing Water Initiative and defined five principles to value water better in decision-making processes. But it has proven very difficult to determine water’s ‘true value’ concluded the UN in their 2021 Valuing Water report. Also the World Bank in its 2024 report on valuing water as a natural asset notes that estimating the value of water is still a challenge, but that adding it to the World Bank’s Changing Wealth of Nations reports would help to underpin the importance of water to the economy and embed water into macroeconomic thinking. The GCEW report still leaves open how approaches and algorithms for valuing water could look like and how this could guide policies, investments and projects on a more sustainable path.

5. Urgent need for coordinated global efforts to address the looming water crisis

Despite the interconnectedness of the global green and blue water systems and the important interlinkages with climate change and biodiversity, the looming water crises still lacks global governance structures for water. In stark contrast with other environmental UN conventions the UN has held only two water conferences in the past 50 years and only very recently launched the UN System-wide Strategy on Water and Sanitation and appointed an UN Special Envoy for Water. Given the critical trends from global to local, the GCEW urges to take immediate steps to improve the global governance on water and proposes:

- to support the development of global water governance in order to value water as an organizing principle. The global hydrological cycle, encompassing both blue and green water, should be valued and governed as a collective and systemic challenge.

- to launch five missions areas on a global scale to strengthen the role of water:

– Mission 1 Launch a new revolution in food systems.

– Mission 2 Conserve and restore natural habitats critical to protect green water.

– Mission 3 Establish a circular water economy.

– Mission 4 Enable a clean-energy and AI-rich era with much lower water intensity.

– Mission 5 Ensure that no child dies from unsafe water by 2030. - to establish a Global Water Pact that sets clear and measurable goals for water and to protect and stabilize the hydrological cycle in order to safeguard the world’s most valuable resource.

With a focus on five global missions, the GCEW expects that a concrete framework for developing public-private-people coalitions can be started, drawing on diverse expertise and engaging all sectors and voices. The global water missions obviously intertwine with many other crucial environmental management strategies, such as the global biodiversity strategy, protecting the natural areas and biodiversity (Convention on Biological Biodiversity – CBD) and the framework to cope with climate change. Therefore, as part of the way forward, the GCEW states that is it will be required to anchor the value of the water cycle by commitments in every other convention, including those on climate, biodiversity, wetlands, and desertification.

In this respect, a first positive step was taken during the otherwise disappointing Climate COP29 in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. Here, the Declaration on Water for Climate Action, including the Baku Dialogue on Water for Climate Action, was endorsed by almost 50 countries and a number of global non-state actors. This declaration commits to taking integrated approaches to combat the causes and impacts of climate change on water basins, to greater regional and international cooperation, and to continuity in addressing the water-climate challenges between COPs.

Conclusion and future steps – will the UN pick up the gauntlet?

Following many preceding studies and the UN 2023 Water Conference, the GCEW made another attempt in keeping the attention for water on a high level across the world. The Commission confirmed that water plays a pivotal role for the economy, human well-being and natural ecosystems. The commission underpinned the vital importance of the global water cycle through both ‘green and blue water’ as a global common good, providing new legitimacy for managing transboundary hydrological systems, while acknowledging the interaction of water with climate, land use and nature areas. Furthermore, an improved global governance and an economic transformation is called for, reflecting the importance of the global water cycle and the value and scarcity of water. The still conceptual advise however, will fall on dead soil if it will not be transferred into more tangible steps to better protect our freshwater resources and into concrete mechanisms to transform today’s economy into a ‘water-based’ economy.

At the global level, the UN System-wide Strategy on Water and Sanitation and recently appointed UN Special Envoy for Water should unequivocally pick up the gauntlet, keep up addressing the full range of water challenges and shape the global processes across future COP’s. Additional efforts will be needed to break down the global water crisis into the regional to local challenges of Too little, Too much and Too dirty water and practical guidance on how water can be valued better in the day-to-day complex decision-making about managing water resources and water-related risks. Water-based economic mechanisms and coherent goals and targets across all relevant water topics and sectors, therefore are urgently needed to focus policies and stakeholder communities, spur innovation and financing, and structurally bend the trend.

Drs Willem Ligtvoet

Independent advisor Water, Climate and Sustainable development and former Program Leader at the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) for this field of work, on a global, European and national scale. WL was the initiator of The Geography of Future Water Challenges, the overarching PBL program 2016-2023 for the assessment of challenges and solutions (Bending the trend) as to the water and climate risks on a global scale. Trained as a systems ecologist (Leiden University), WL has worked as researcher at the National Institute for Nature Management and the University of Leiden (Mwanza, Tanzania), advisor at Witteveen+Bos (Netherlands, Indonesia, Egypt, Gaza) and as program leader at the PBL and its predecessors.

Drs Vincent van den BergenFormer head Global Affairs in the Dutch Directorate International Affairs at the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment (VROM). Specialized in Climate, Water and Environmental Policy. Currently acting as Chairman of the working group on Political Affairs with Grandparents for Climate in The Netherlands.