STAFF MEMBERS OF ICJ

The World Court…

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. It was established by the UN Charter, signed on 26 June 1945 at San Francisco, in pursuance of one of the primary purposes of the United Nations: “to bring about by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace”.

The Court operates under a Statute which forms an integral part of the Charter, as well as under its own Rules. It started operating in 1946, when it replaced the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ), which had been established in 1920 under the auspices of the League of Nations. The seat of the Court is in the Peace Palace at The Hague. Of the six principal organs of the United Nations, it is the only one not located in New York.

In the field of public international law, the ICJ is the only judicial organ with potentially both general and universal jurisdiction and it is often called “the World Court”. All 193 members of the UN are automatically party to the ICJ. The Court operates on equal footing with the other five organs of the United Nations, namely to bring “by peaceful means, and in conformity with the principles of justice and international law, adjustment or settlement of international disputes or situations which might lead to a breach of the peace”[1]. The official languages of the Court are French and English.

… not to be confused with other International Legal Organizations based in The Hague

t is important to be aware of the growing number of international courts and tribunals based in The Hague that continue to be confused with the ICJ, but which have very different mandates. In addition to the ICJ, the Iran-US Claims Tribunal and the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), The Hague is home to a number of criminal courts and tribunals. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), the Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (SPL) and the Special Tribunal for Sierra Leone (STSL) all have premises in the city. Unlike the ICTY, the ICTR, the ICC, the SPL and the STSL, the ICJ does not have any criminal jurisdiction over individuals. It cannot try individuals and cannot receive cases from individuals, groups or organizations.The Court is, moreover, not a supreme court for national tribunals nor an appeal court for the citizens of the world, as people sometimes assume.

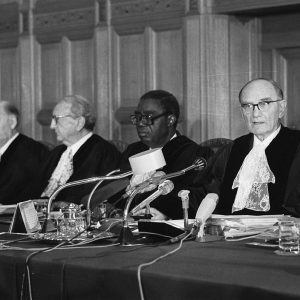

The International Court of Justice in The Hague in session on December 10, 1979

Organisation and Functioning of the Court

The Judges

The Court is composed of 15 judges elected to nine‑year terms of office by the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council (sitting independently of each other). Only a majority in both of these organs will guarantee that a judge be elected. Elections are held every three years for one‑third of the 15 seats, and retiring judges may be re‑elected. The Members of the Court do not represent their governments once elected, but are independent magistrates who make a solemn declaration to exercise their powers impartially and conscientiously. In accordance with Article 2 of the Court’s Statute, the Bench must be “composed of a body of independent judges, elected regardless of their nationality from among persons of high moral character, who possess the qualifications required in their respective countries for appointment to the highest judicial offices, or are jurisconsults of recognized competence in international law”.

All States parties to the Statute of the Court have the right to propose candidates. These proposals are made not by the government of the State concerned, but by a group consisting of the members of the Permanent Court of Arbitration designated by that State, (i.e. by the four jurists who can be called upon to serve as members of an arbitral tribunal under the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907).

Each group can put forward up to four candidates, of whom not more than two may be of its own nationality, whilst the others may be from any other country. The Court may not include more than one national of the same State. In addition to which, the Court as a whole must reflect the main types of civilization and the principal legal systems of the world. This principle is reflected in the distribution of membership of the Court among the principal regions of the world. Currently there are 3 African judges, 2 judges from Latin America and the Caribbean, 3 from Asia, 5 from Western Europe and other States (in particular, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand), and 2 from Eastern Europe. Although there is no entitlement to membership on the part of any country, the Court has always included judges of the nationality of the permanent members of the Security Council.

The current composition of the Court is as follows. President: Peter Tomka (Slovakia); Vice-President: Bernardo Sepúlveda‑Amor (Mexico); Judges: Hisashi Owada (Japan), Ronny Abraham (France), Kenneth Keith (New Zealand), Mohamed Bennouna (Morocco), Leonid Skotnikov (Russian Federation), Antônio A. Cançado Trindade (Brazil), Abdulqawi A. Yusuf (Somalia), Christopher Greenwood (United Kingdom), Xue Hanqin (China), Joan E. Donoghue (USA); Giorgio Gaja (Italy), Julia Sebutinde (Uganda), and Dalveer Bhandari (India).

Judges come from very different professional backgrounds and have varying expertise. Some are professors, others national judges, former diplomats or former legal advisers to their national governments. This mix of professional experience is enriching for the Court in its decisions making processes. In situations where the Court does not include a judge possessing the nationality of a State party to a case, that State may appoint a person to sit as a judge ad hoc for the purpose of the case. Judges ad hoc sit on terms of complete equality with elected judges for those particular proceedings. Once elected, judges ad hoc take the same oath as the Members of the Court.

The Registry

The Court has its own secretariat, the Registry, which is headed by the Registrar, Mr. Philippe Couvreur from Belgium. He was elected, in accordance with Article 22 of the Rules of Court, in a “secret ballot from among candidates proposed by Members of the Court” for a term of seven years. Registrars may be re-elected; Mr. Couvreur is currently serving his second term of office.

The Registrar carries out diverse duties, set out in Article 26 of the Rules of Court, with the assistance of some 120 staff members. He is responsible for all departments and divisions of the Registry. His role is threefold: judicial, diplomatic and administrative.

The Registrar’s judicial duties notably include those relating to the cases submitted to the Court. The Registrar performs, among others, the following tasks: (a) he keeps the General List of all cases and is responsible for recording documents in the case files; (b) he manages the proceedings in the cases; (c) he is present in person, or represented by the Deputy‑Registrar, at meetings of the Court and of the Chambers; he provides any assistance required and is responsible for the preparation of reports or minutes of such meetings; (d) he signs all judgments, advisory opinions and orders of the Court, as well as minutes; (e) he maintains relations with the parties to a case and has specific responsibility for the receipt and transmission of certain documents, most importantly applications and special agreements, as well as all written pleadings; (f) he is responsible for the translation, printing and publication of the Court’s judgments, advisory opinions and orders, the pleadings, written statements and minutes of the public sittings in every case, and of such other documents as the Court may direct to be published; and (g) he has custody of the seals and stamps of the Court, of the archives of the Court, and of such other archives as may be entrusted to the Court (including the archives of the Permanent Court of International Justice and of the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal).

The Registrar’s diplomatic duties include the following tasks: (a) he attends to the Court’s external relations and acts as the channel of communication to and from the Court; (b) he manages external correspondence, including correspondence relating to cases, and provides any consultations required; (c) he manages relations of a diplomatic nature, in particular with the organs and States Members of the United Nations, with other international organizations and with the Government of the country in which the Court has its seat; (d) he maintains relations with the local authorities and with the press; and (e) he is responsible for information concerning the Court’s activities and for the Court’s publications, as well as for press releases, among other things.

The Registrar’s administrative duties include: (a) the Registry’s internal administration; (b) financial management, in accordance with the UN’s financial procedures, and in particular preparing and implementing the budget; (c) the supervision of all administrative tasks, including printing; and (d) making arrangements for such provision or verification of translations and interpretations into the Court’s two official languages (English and French) as the Court may require.

Session of the International Criminal Court taking place in the Great Hall of the Peace Palace

Role of the Court

The Court has a twofold role:

- to settle, in accordance with international law, legal disputes between States (contentious function); and

- to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by duly authorized UN organs and agencies (advisory function).

Contentious cases

In contentious cases, only States may apply to and appear before the Court. The Member States of the United Nations are so entitled. The Court has no jurisdiction to deal with applications from individuals, from non-governmental organizations or private groups and it rules only on the rights and obligations of States.

The Court is competent to entertain a dispute only if the States concerned have accepted its jurisdiction in one or more of the following ways:

- by the conclusion between them of a special agreement to submit the dispute to the Court;

- by virtue of a jurisdictional clause, i.e., typically, when they are parties to a treaty containing a provision whereby, in the event of a disagreement over its interpretation or application, one of them may refer the dispute to the Court. Over 300 treaties or conventions contain a clause to such effect;

- through the reciprocal effect of declarations made by them under the Statute whereby each has accepted the jurisdiction of the Court as compulsory in the event of a dispute with another State having made a similar declaration. The declarations of 66 States are at present in force, a number of them having been made subject to the exclusion of certain categories of dispute. In cases of doubt as to whether the ICJ has jurisdiction, it is the Court itself which decides.

Procedures

Written and Oral Phases

The ICJ decides in accordance with international treaties and conventions in force, international custom, general principles of law and, as subsidiary means, judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists.

The procedure followed by the Court in contentious cases includes a written phase, during which the Parties to a case present their arguments in written form. Different rounds are possible (memorial/counter-memorial and rejoinder/reply). This process can be very lengthy, depending on the complexity of the case (and may include thousands of pages). Following the written phase, the oral phase consists of public hearings. During the oral phase it is not usual to interrupt pleadings of the Parties with questions from the bench. But the application of the judges’ right to put questions at the end of a hearing session has increased. Parties are given the opportunity to reply to these questions either in writing or orally.

As a universal institution, the Court generally exercises its functions as a full court. However, at the request of the parties, a case may be brought before a Chamber.

Deliberations and judgment

Once the oral phase is closed, judges begin deliberations. The deliberations of the Court are collegial. All members of the Court are involved at every stage of the process of drafting a judgment. The judgment is rendered, in general, between 6 to 9 months after the end of the hearings.

The Court deliberates in camera. Following the deliberations, it delivers a judgment, which is binding, final and without appeal for the parties to a case in open session. Cases of non-compliance are extremely rare. In the exceptional case that one of the States involved fail to comply with the decision of the Court, the other State may lay the matter before the UN Security Council, which is empowered to recommend or decide upon the measures to be taken to give effect to the judgment. Since 1946, the ICJ has delivered 113 judgments on disputes concerning, inter alia, land frontiers, maritime boundaries, territorial sovereignty, the non‑use of force, violation of international humanitarian law, non‑interference in the internal affairs of States, diplomatic relations, hostage taking, the right of asylum, nationality, guardianship, rights of passage and economic rights.

Advisory Opinions

The advisory procedure of the Court is open solely to international organizations. The only bodies at present authorized to request advisory opinions of the Court are five organs of the United Nations and 16 agencies of the UN family. On receiving a request, the Court decides which States and organizations might provide useful information and gives them an opportunity of presenting written or oral statements. The Court’s advisory procedure is otherwise modelled on the contentious proceedings, and the sources of applicable law are the same. In principle, the Court’s advisory opinions are consultative in character and are therefore not binding as such on the requesting bodies. Certain instruments or regulations can, however, provide in advance that the advisory opinion shall be binding.

Since 1946, the Court has given 27 Advisory Opinions, concerning, inter alia, the legal consequences of the construction of a wall in the occupied Palestinian territory, admission to United Nations membership, reparation for injuries suffered in the service of the United Nations, the territorial status of South‑West Africa (Namibia) and Western Sahara, judgments rendered by international administrative tribunals, expenses of certain United Nations operations, applicability of the United Nations Headquarters Agreement, the status of human rights rapporteurs, and the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons.

2014: Official visit to the International Court of Justice of the Under-Secretary-General, the Legal Counsel of the United Nations, Mr. Miguel de Serpa Soares.

Unique mandate

The Court is vested with a unique mandate under the UN Charter as the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. In exercising its judicial functions, the ICJ is often called upon to defuse crisis situations, to help normalize relations between States and to reactivate negotiation processes which had been at a standstill. It is a unique judicial institution, whose role is to deal with the legal problems of the international community as a whole. The Court is a key part of the mechanism for maintaining international peace and security established by the Charter of the United Nations.

In short, the ICJ discharges the principal responsibility for delivering international justice under the UN system by peacefully settling the bilateral disputes submitted to it by States. An area where tensions between States may escalate into an open conflict, should the underlying disagreement not be referred to the Court, undoubtedly resides in land and maritime boundary disputes.

The ICJ has developed a particularly strong reputation in adjudicating those types of contentious proceedings, with parties invariably putting their confidence in the prospect of the Court reaching an equitable solution that will in turn normalise relations between them. Such examples are numerous. In the recent past, the Court delivered a Judgment resolving a boundary dispute between Burkina Faso and Niger, which both Parties have praised and which no doubt contributed to further strengthening their mutually respectful and harmonious relations. Another case, namely that of the Maritime Dispute opposing Peru and Chile, is currently under deliberation. The future ICJ Judgment will settle a long-standing dispute over the maritime frontier between the two States and, one hopes, appease the tensions that have arisen between them as a result of their conflicting maritime claims.

The ICJ is increasingly resorted to as a forum for the adjudication of environmental disputes – particularly those that involve transboundary harm – and other disagreements affecting the conservation of living resources, the protection of the environment or engendering potentially adverse effects on human health. Such concerns were central in the Court’s adjudication of the case concerning Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), in which it delivered its Judgment in 2010. The Court’s current docket also follows suit in two cases where scientific evidence will play a key role: the case concerning Whaling in the Antarctic (Australia v. Japan: New Zealand intervening) and the case concerning Aerial Herbicide Spraying (Ecuador v. Colombia).

By its advisory opinions, the ICJ, in particular, contributed to the decolonization of certain territories. For example, in 1950 the Court held that South Africa could not unilaterally change the international status of the territory of South West Africa (the present Namibia) by absorbing it, in breach of the League of Nations Mandate given to it after the First World War, under which South Africa was to administer the territory on behalf of the League for the benefit of its inhabitants. In 1971, the Court went further, paving the way to Namibia’s independence. In an advisory opinion given at the request of the Security Council after the General Assembly had decided that the mandate for South West Africa had come to an end, it declared that the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia was illegal and had to be terminated as soon as possible.

The Court’s contribution to international law

In fulfilling its mandate, the Court not only contributes to strengthening the role of international law in international relations, but also to the development of that law. Despite the fact that it cannot create new laws in the same way as a regulator, the Court can clarify, refine and interpret the rules of international law. Since all the Court’s decisions are authoritative, their effect reaches well beyond the parties to the cases before it. All States and international organizations take them into account, and they serve as guidelines for their international conduct. Furthermore, the organs entrusted with the codification of international law – such as the International Law Commission of the United Nations – refer frequently to the Court’s decisions.

The Court’s future

The ICJ was conceived by States. Hence its future ultimately depends on them. States established the World Court in 1945, States have the power to ratify amendments to its Statute, and, by accepting the Court’s compulsory jurisdiction, it is again States who contribute to the Court’s authority and activity.

Notes

[1]United Nations Charter, Article 1, para. 1

The summary was written by the editors of VN Forum.